Tetanus

Key facts

-

Tetanus is a rare but serious disease of the nervous system. It is caused by bacteria that are mostly found in soil, manure and dust.

-

It causes severe muscle contractions and affects the muscles used for breathing.

-

Overall, about 13% of people who catch tetanus in Australia will die. The risk is greatest for people who are very young and older people.

-

In Australia, all infants and young children are recommended to be vaccinated against tetanus. To keep this level of protection for adolescents, a booster dose is recommended for all 12- and 13-year-olds. This booster is the best way to protect adolescents from tetanus.

On this page

- What is tetanus?

- What will happen to my adolescent if they catch tetanus?

- What vaccine will protect my adolescent against tetanus?

- When should my adolescent be vaccinated?

- How do tetanus vaccines work?

- How effective are tetanus vaccines?

- Will my adolescent catch tetanus from the vaccine?

- What are the common reactions to the vaccine?

- Are there any rare and/or serious side effects to the vaccine?

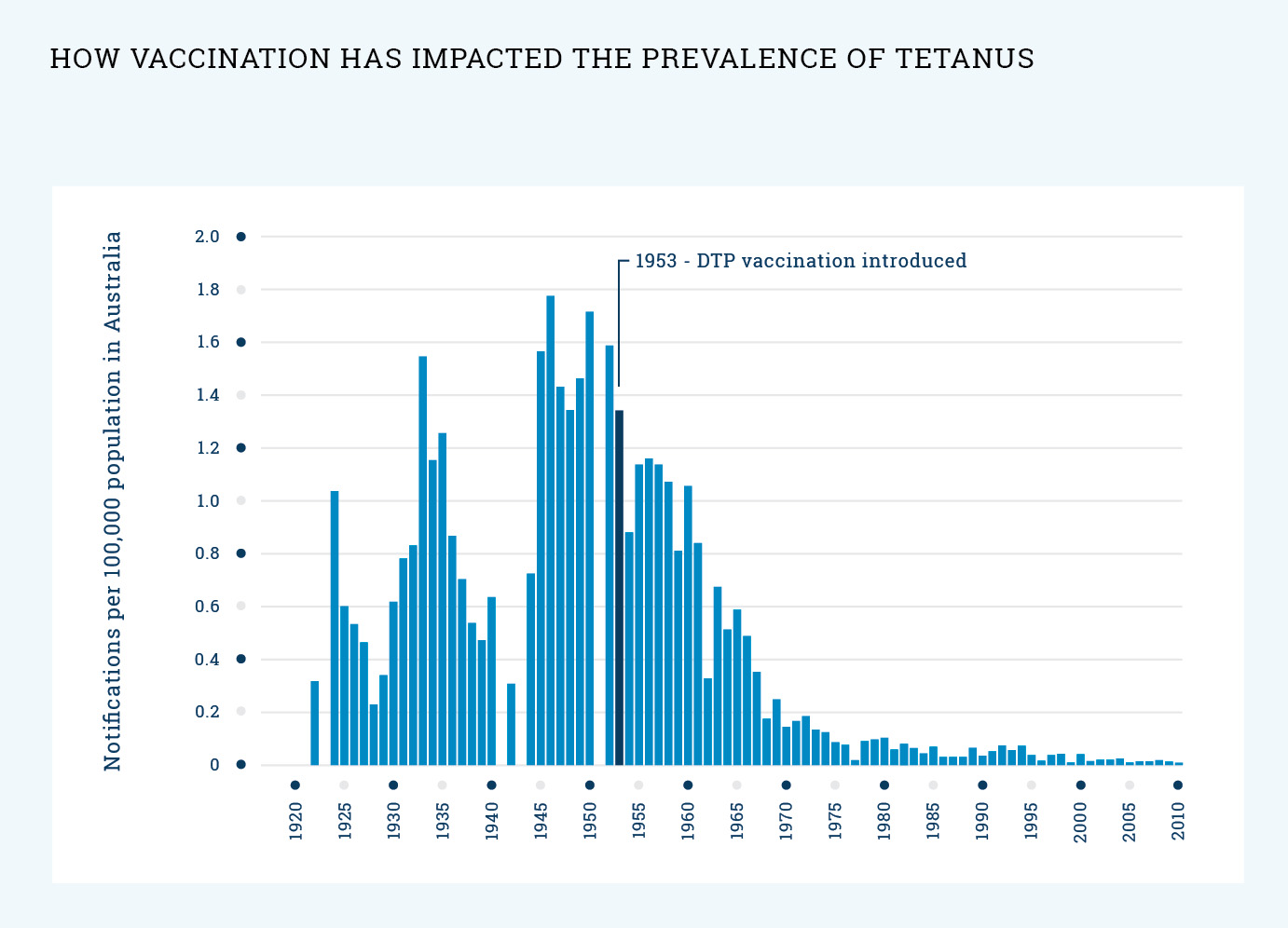

- What impact has vaccination had on the spread of tetanus?

- What if I still have questions?